In September 2020, Brown University accused students of lying about their location; e.g.:

What was Brown’s basis for these accusations?

In an interview with The Brown Daily Herald, University Spokesperson Brian Clark said the University evaluated a variety of indicators, including:

- indications of building access,

- indications of accessing private electronic services,

- indications of accessing secure networks, and

- reports from community members.

The mechanics of that last indicator are pretty self-explanatory, but what about the others? Canvas doesn’t Want To Know Your Location. In this post, I’m going to break down the technical mechanisms behind each of these indicators.

For the most part, I do not have insider knowledge on how Brown reached its decisions. Rather, I’m going to consider each of the indicators Brian Clark named, and describe the technical mechanisms to which Brown could have availed itself to generating location data.

Indications of Building Access

This is an easy one. Brown’s buildings are located on Brown’s campus. Brown’s campus is in Providence. If you are in Brown’s buildings, you are on Brown’s campus, in Providence. QED.

At Brown, building access is primarily regulated with electronic control systems (namely Software House’s C•CURE 9000 system), not mechanical keys.

Encoded on track 2 of the magnetic stripe on every University ID card is a sixteen digit number that uniquely identifies the card:

Well, that’s underwhelming — of course you can’t see it! However, up until 2017 or 2018, this number was also printed on the front of ID cards, just above the card-holder’s name:

This pseudo-random identifier (well, its last ten digits) are what uniquely identify you whenever you swipe your Brown ID card anywhere. And, if you lose your Brown ID card, this is the only thing that’s changed when you’re issued a replacement. Convenient! In contrast, when you lose your dorm room’s mechanical key, Brown must replace (or rather, rekey) the locks.

But, also unlike a mechanical key, every swipe of a Brown ID card is logged in a central database. The C•CURE 9000 lets administrators view the complete historical building access history of a person. Last Spring, Brown used this mechanism to identify and prod students who were slow to evacuate Providence.

Indicators from Electronic Services

University web services like Canvas don’t directly ask you for your location. Nonetheless, accessing these services leaves a location finger print: your IP address.

Your IP address is a number that identifies your device (computer, phone, etc.) for the purposes of network routing. In principle, nobody but you and your internet provider know the exact mapping of your IP address to your physical address.

In practice, IP addresses can be used to roughly geolocate a device. Batches of IP addresses are associated loosely with geographic areas. Since every web service access leaves an IP address as a trace, there are tremendous incentives for advertisers to be able accurately identify what city or town an IP address is probably associated with.

Brown probably isn’t analyzing the access logs of its individual web services (like Canvas). Rather, they need only to audit the access logs of its three identity access management (IAM) systems:

- The Google Workplace IAM system is used to control access to your @brown.edu email, and to the various Google Drive services. Google Workplace provides administrators with login audit logs that include users’ IP addresses.

- The Shibboleth IAM system controls access to all other Brown web services, such as Canvas. It’s what you think of as your “Brown account”. Shibboleth is very flexible, and can be configured to log IP addresses.

- DUO is used to provide two-factor authentication for Shibboleth logins. It too provides administrators with detailed access logs.

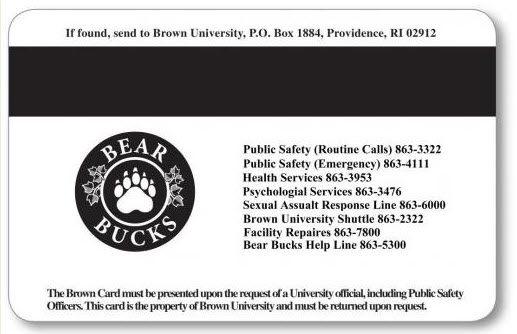

You can partly view your Google Workplace login history for yourself by opening your Brown email and clicking “Details” in the bottom right-hand corner of the page; e.g.:

With either of these access logs in hand, Brown could then turn to any number of geolocation services (like this one) to guess your physical location.

Indicators from Secure Networks

This is another easy one. Brown’s WiFI network blankets Brown’s campus. Brown’s campus is in Providence. If you are on Brown’s WiFi network, you are on Brown’s campus. QED.

What might surprise you is the sheer depth of surveillance that’s capable with WiFi alone. This section will barely scratch the surface.

Identification

Brown’s WiFi routers each broadcast three service sets:

The Brown and eduroam networks require that you authenticate with your Brown account credentials. Brown University is thus able to identify the owner of any device connected to these networks.

While Brown Guest does not require authentication, it still provides mechanisms of identification. Your network devices broadcast a unique identifier called a MAC address.

Brown maintains databases of the MAC addresses of all connected devices.

If you have ever connected to an authenticated network, Brown will be able to de-anonymize your connections to Brown Guest — unless your device implements MAC address randomization, which (as the name suggests) randomizes your device’s MAC address on a per-network basis.

Localization

Brown’s access points log the MAC addresses of the devices that have connected to them. As of 2015, Brown retained these logs for at least several years — possibly indefinitely. Since there are so many access points on campus, which access point you are connected to can narrow your location down to a particular room. Combined, these logs paint a very accurate picture of your location on campus at any time.

You do not need to be actively browsing the internet for Brown to know where you are via this mechanism. As you walk through campus, your phone likely automatically reconnects to the nearest available access point. If you are within a literal stone’s throw of campus, you should assume that Brown can (roughly) identify your location.

A 2016 class project did precisely this, with three million (anonymized) connection records collected over a year from just 49 access points across campus:

Furthermore, if you are in range of three or more of Brown’s ARUBA access points, Brown can, in principle, precisely triangulate your location. This functionality is common in enterprise-grade WiFi infrastructure. (If you’ve ever tried to run a “rogue” WiFi router in your dorm room and receive an angry knock on your door — this is the mechanism by which you were located.)

How do I find out more?

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act empowers students to request their education records from their University.

If you are a current Brown student and would like to go beyond my blog post and learn exactly how Brown University knows your location, file a FERPA request. Brown University is obligated to respond within 45 days. You’ll need to be specific with your request. I suggest requesting:

- the timestamps, MAC addresses and BSSIDs associated with your devices’ connections to Brown University’s wireless access points

- the timestamps and locations associated with all building accesses conducted with your ID card

- the login audit data associated with all Google Workplace, Shibboleth, and DUO authentications conducted by your accounts

Additionally, the General Data Protection Regulation gives EU citizens and residents expansive control over how their personally identifiable information (PII) is used, and the right to request a copy of or the destruction of collected data. I believe these requests should be directed to Brown’s compliance office. You might be able to do this even if you’re a Brown alumni.

If you attempt either of these steps, please get in touch! I’m very curious as to what Brown is actually doing.

Bonus: Surveillance Cameras

As of February 2020, eight hundred surveillance cameras monitor campus 24/7. Brown has as about as many surveillance cameras as it has full-time faculty! This map documents a mere seven percent of Brown University’s total camera surveillance capacity:

This map displays data from OpenStreetMap. Help improve its accuracy!Brown University has a longstanding policy governing the appropriate uses of its surveillance cameras. Unfortunately, this policy is secret.

While Brown probably does not currently have the capacity to both broadly and deeply inspect the firehose of data produced by these cameras, this may change in the near future. Axis Communications, Brown’s primary supplier of surveillance cameras, now touts cameras that can perform on-board facial recognition. And Software House, the provider of the C•CURE 9000 access control system, has begun marketing the integration of facial recognition with its access control systems: